E.G.R. Cordingley launched his series of Limited Editions in the Summer of 1933 shortly after sending a letter to The British Chess Magazine, (May 1933, page 204), deploring the loss of the game scores from many tournaments, and appealing for a "Circle of Chess Votaries" willing to support his scheme for printing the games from interesting events. His first book covered the Hastings Christmas Tournament 1932-33 and only 30 copies were printed.

Cordingley's second Limited Edition on Frankfurt 1930 was published in an edition of 40 copies towards the end of 1933 and he again wrote to The British Chess Magazine, (November 1933, page 505), seeking a permanent body of subscribers on whose support he could rely. At the time he had 28 subscribers, and this had increased to 47 when his third book, on Liege 1930, was published in the Spring of 1934 with 61 copies.

It seems that Cordingley's intention in printing such small numbers of his earliest books was simply to cover the costs of supplying the demand of his modest circle of subscribers. However, in his very interesting article; E.G.R Cordingley, Publishing Pioneer, in the December 1999 issue of Chess, Ken Whyld commented that his friend and associate "saw that by limiting and numbering his publications, his customers were assured that their investments would not depreciate, and indeed he offered to buy back at the original price"

Whatever his motives, the growth in interest in chess tournament publications has resulted in these very limited editions becoming rare, sought after and expensive. Cordingley sent a complimentary copy of his Hastings 1932/33 book to The British Chess Magazine in 1933 and this very copy turned up in a chess book auction in 2007 when it sold for around €250. (Antiquariat A.Klittich-Pfankuch, June 2007, lot 818)

I do not possess any of the earliest Limited Editions, my first is number 7 in the series, Moscow 1935, volume I, published in May 1935, 250 copies.

In his Foreword, Cordingley acknowledges the assistance provided by R. N. Coles and Dr. Lloyd Storr-Best who translated the notes from the Russian daily bulletins and also wrote the Preface painting the background to the tournament and describing the extraordinary interest it generated in Moscow. 4,000 spectators filled the playing hall every day. Cordingley also offered to buy back copies of his first three books, and mentioned that only about 25 people possess the complete set of his Limited Editions.

Volume I of Moscow 1935 covers the first ten rounds of this famous tournament, after which Botvinnik was leading ahead of Flohr, Em. Lasker, Levenfish, Ragosin, Capablanca etc. Here is the game between Botvinnik and Stahlberg in Round 7.

Number 10 in the series is Moscow 1936 and I have a subscriber's copy which is numbered and signed by Cordingley. Subscriber's copies also included the vignette shown at the top of this article.

The title page includes details of Cordingley's American Agent, Fred Reinfeld, and Ken Whyld states in his Chess article that Limited Editions 4 to 10 (excluding No. 9) were produced jointly with Reinfeld; in fact Cordingley No. 8 and Reinfeld No. 3 on Margate 1935 are the same book. Cordingley No. 9, on Dresden 1936, was a German publication reissued with an English title page.

In Moscow 1936, most games are given in Continental notation with notes at the end, making the games a little difficult to follow smoothly.

The book includes four pages of adverts for chess books, and the List of Subscribers has many familiar names:

There was no No. 11 in the series but when Ken Whyld purchased Cordingley's library in 1952 he found that it included the stencils for Budapest 1921 which he supposed were intended to be used for No. 11. Whyld completed this work and published the pamphlet in 1953 as the last of Cordingley's Limited Editions of Tournament Books.

I do not possess any of the earliest Limited Editions, my first is number 7 in the series, Moscow 1935, volume I, published in May 1935, 250 copies.

In his Foreword, Cordingley acknowledges the assistance provided by R. N. Coles and Dr. Lloyd Storr-Best who translated the notes from the Russian daily bulletins and also wrote the Preface painting the background to the tournament and describing the extraordinary interest it generated in Moscow. 4,000 spectators filled the playing hall every day. Cordingley also offered to buy back copies of his first three books, and mentioned that only about 25 people possess the complete set of his Limited Editions.

Volume I of Moscow 1935 covers the first ten rounds of this famous tournament, after which Botvinnik was leading ahead of Flohr, Em. Lasker, Levenfish, Ragosin, Capablanca etc. Here is the game between Botvinnik and Stahlberg in Round 7.

Number 10 in the series is Moscow 1936 and I have a subscriber's copy which is numbered and signed by Cordingley. Subscriber's copies also included the vignette shown at the top of this article.

The title page includes details of Cordingley's American Agent, Fred Reinfeld, and Ken Whyld states in his Chess article that Limited Editions 4 to 10 (excluding No. 9) were produced jointly with Reinfeld; in fact Cordingley No. 8 and Reinfeld No. 3 on Margate 1935 are the same book. Cordingley No. 9, on Dresden 1936, was a German publication reissued with an English title page.

In Moscow 1936, most games are given in Continental notation with notes at the end, making the games a little difficult to follow smoothly.

The book includes four pages of adverts for chess books, and the List of Subscribers has many familiar names:

There was no No. 11 in the series but when Ken Whyld purchased Cordingley's library in 1952 he found that it included the stencils for Budapest 1921 which he supposed were intended to be used for No. 11. Whyld completed this work and published the pamphlet in 1953 as the last of Cordingley's Limited Editions of Tournament Books.

No. 12 is Amsterdam 1936 published in 1937 in a smaller format.

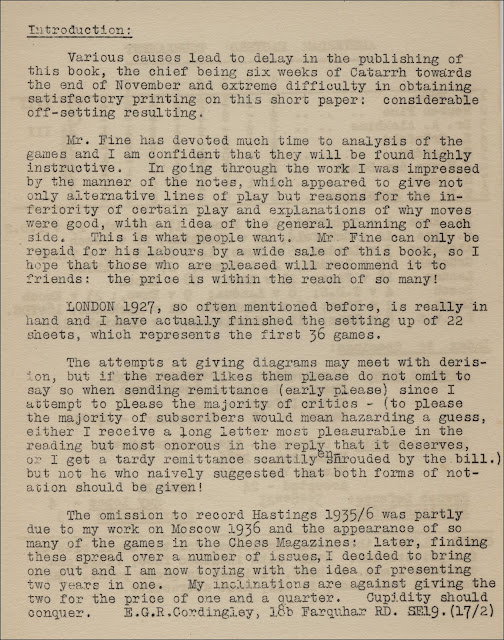

Cordingley engaged Reuben Fine, the joint winner, to analyse and annotate the games and, this time the notes were interspersed within the moves, making the games easier to follow. However, Cordingley's method of production, i.e. a standard typewriter, precluded normal chess diagrams, and grids with letters were the best that he could manage. These were difficult to fathom and probably received the derision that he had anticipated in his Introduction to this book.

Although the 28 games are extensively annotated, there is no overall commentary on the eight-player tournament, won by Fine and Euwe ahead of Alekhine.

The List of Subscribers had grown to 76 entries.

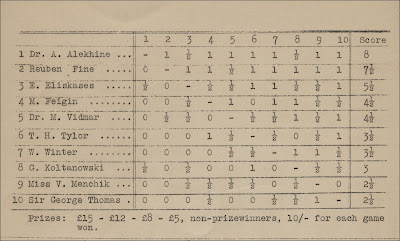

Next off the typewriter was Hastings 1936-37, won by Alekhine ahead of Fine and Eliskases.

This 30-page publication was back to a larger format, and notes to the 45 games were taken from The British Chess Magazine and Chess. There is no introductory matter except for a cross table and index of openings.

The book includes four of the awkward diagrams and a few adverts are squeezed in. The List of Subscribers had reached 80.

Incidentally, the numbers of copies printed according to Betts' Bibliography is not always correct. Moscow 1935 and Moscow 1936 both had 250 copies not 240 as stated in Betts, Amsterdam 1936 had 280 copies not 265 and Hastings 1936-37 had 180 copies not 140. I have amended the table given in a previous article and I shall be pleased to hear of any other discrepancies.

© Michael Clapham 2019

Cordingley engaged Reuben Fine, the joint winner, to analyse and annotate the games and, this time the notes were interspersed within the moves, making the games easier to follow. However, Cordingley's method of production, i.e. a standard typewriter, precluded normal chess diagrams, and grids with letters were the best that he could manage. These were difficult to fathom and probably received the derision that he had anticipated in his Introduction to this book.

Although the 28 games are extensively annotated, there is no overall commentary on the eight-player tournament, won by Fine and Euwe ahead of Alekhine.

The List of Subscribers had grown to 76 entries.

Next off the typewriter was Hastings 1936-37, won by Alekhine ahead of Fine and Eliskases.

This 30-page publication was back to a larger format, and notes to the 45 games were taken from The British Chess Magazine and Chess. There is no introductory matter except for a cross table and index of openings.

The book includes four of the awkward diagrams and a few adverts are squeezed in. The List of Subscribers had reached 80.

Incidentally, the numbers of copies printed according to Betts' Bibliography is not always correct. Moscow 1935 and Moscow 1936 both had 250 copies not 240 as stated in Betts, Amsterdam 1936 had 280 copies not 265 and Hastings 1936-37 had 180 copies not 140. I have amended the table given in a previous article and I shall be pleased to hear of any other discrepancies.

© Michael Clapham 2019